[themify_quote]

Art today is a kind of instrument, an instrument for modifying consciousness and organising new modes of sensibility. And the means for practising art have been radically extended. Indeed in response to this new function (more felt than clearly articulated), artists have to become self-conscious aestheticians: continually challenging their means, their materials, and methods. Often, the conquest and exploitation of new materials and methods drawn from the world of ‘non-art’ – for example, from industrial technology, from commercial processes and imagery, from purely private and subjective fantasies and dreams – seems to be the principal effort of many artists.

Susan Sontag

[/themify_quote]

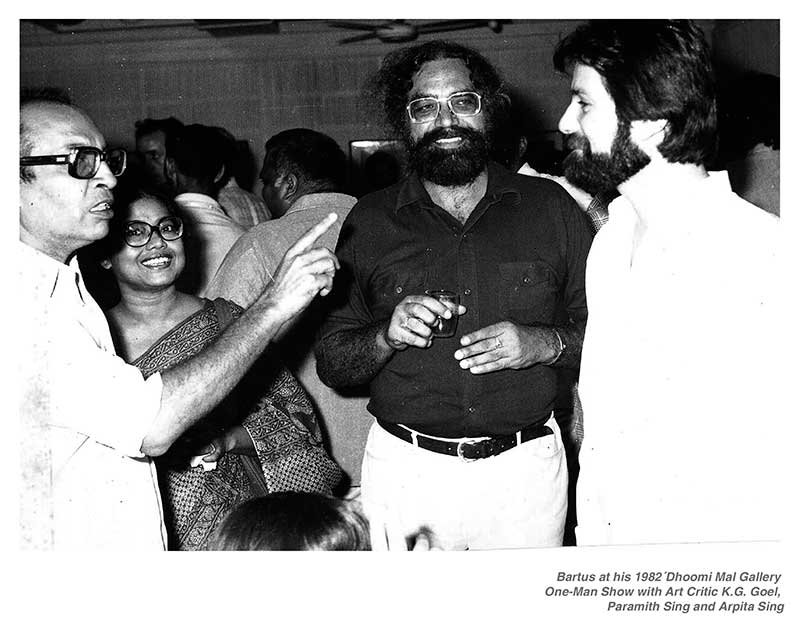

Bartus Bartolomes, a Venezuelan artist whose first one-man show in India at the Dhoomimal Gallery which folded on 6 September, is an artist representing the quintessence of this new sensibility in arts: he is truly a self-conscious aesthetician whose emergence in the late Fifties Susan Sontag celebrates. He is inventive in the use of collage which in his hands is more than a method of combining and pasting elements: he has the sensitivity of a Kandinsky colour game which he uses with the science of Mondrian insight. In his work there is a resonating interplay of the whole key board of sense and consciousness. His work reminds us of the truth of McLuhan: the content is the technology peculiar to each medium and its effect. He calls his collage-like constructions ‘icons’ which, “are brief previews of a much larger research project… the Archaeology of the Sign – an approach to iconography through collage, Chinese ink, polychromat paper, letter-set, etc. and (through these) to (investigate) geometrical or symbolical possibilities of the infinite and abstract world

That is to say, the visual units in a collage cannot have both functions: the added objects both configurate simultaneously into form and reference. When the pasted objects form into a relationship and interlock themselves into the surface of the collage their individual referential potential is lost: or the relationships created between the objects have such homogeneity that it survives only momentarily so that an individual object is no sooner recognised that one is forced to let it go. In that situation the gestalt is broken but readjusted again in terms of another gestalt – this time if not in terms of form then in terms of reference. The result is that the viewer is pushed into searching for a common denominator between reference and form.

Bartus, it seems, is interested in questions of form only because in most works the material objects added to the coloured surface do not have a strong referential value. Shapes he employs are simple; they have the simplicity of geometric forms. Rather they are unitary forms which easily do not lend themselves into any experiential relationships and for this reasons they are bound more coherently and individually together. His sensibilities, his eye, having been educated in the aesthetic of Minimalism, the pictorial field is optically vibrant and evokes an internal space that is more than literal. Such a paradigm is undoubtedly limited in scope, and this he turns into great advantage; what seems to preoccupy him is not so much the referential aspect of the icons but the relationship of colour to a specific shape poised as they are between the inside and outside.

Susan Sontag, an internationally known literary (and art) critic, agrees with Harold Rosenberg that contemporary paintings are themselves acts of criticism as much of creation. And, according to Rosenberg, one of McLuchan’s contributions has been to help dissolve the craft-oriented concept that “modern art works still belong in the realm of things contemplated instead of being forces active in the unified field of electric all-atoneness’ of tomorrow’s world community”. Sontag argues against the heavy burden of content in a work of art: this pre-eminence of content is aligned, according to her, to a concept of culture whose true representative is Mathew Arnold (in which the central cultural act is the making of literature, which in itself is understood as the criticism of culture). Putting it another way: in the Arnoldian ambience culture is defined as the criticism of life as en embodiment of moral, social and political ideas, while the new modernist sensibility urges us to look upon art as an extension of life, that is to say, as a mode of representation of life’s vivacity, its powers of sublimation: for we are what we are able to see, hear, taste, smell and feel.

All that is required for enjoying a work of art is our willingness to shed our previous pictorial prejudices; for if one has a good eye then that is enough: It is a kind of seeing with eyes open and thinking, and therefore participating. Bartus is not interested in what kind of evidence our eyes provide us with. And since collage is not an authentic object (neither can it be thought of as fake) it does not have the same aura as that of a painting. Walter Benjamin in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” argues that it is material to the condition of a traditional work of art – a painting say – that it be authentic because the authenticity of a work is its aura which photographs and collages lack. What can never be reproduced is precisely this aura. (Which is the authentic one among the multitude of prints taken from a given negative? Or if a collage is de-collaged – all its visual bits that do not belong to the surface but were glued to it are taken out of it and then reassembled again – Where is one to locate its authenticity?) Since in a collage the referential interest is configuration – the relation between the added visual units – the extra-pictorial objects may or may not depend on each other. Not a wrong approach this, for there is no room for an internal contradiction. That only shows how well Bartus has learnt his Minimal lesson.

If a metaphoric justification is needed this is it: the infinite is represented in a finite shape. The specific essence of his visual calculus is the algebra of the geometric shape; he does it so well that we are moved unconsciously to calculate, add and substract. But surely we are unable to decide whether this is the algebra of thought or feeling. The technology of assemblage is spellbinding: we find ourselves helpless to decide whether collage of the kind Bartus makes with limited intentionality are easier to participate in or to describe.

By K. B. Goel.

Patriot, September 09, 1982